The Unread Library Effect & Mike Lindell's Cyber Symposium

Extremism Goes Along With the Unread Library Effect & the Dunning-Kruger Effect

“Ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge.” - Charles Darwin

We humans are largely an irrational species and often willfully ignorant. One aspect of our ignorance is our proclivity towards believing that we know that which we do not know and our tendency to ignore this fact. We know better, but we choose to remain ignorant of our ignorance.

While believing we know more than we actually know (the Dunning-Kruger effect), we engage in the logical fallacy some call the unread library effect. It’s like believing that something is factually correct because you believe that books on a shelf confirm your belief despite having never read the books.

Zealotry seems to give one blind-spots. It could be political zealotry, or religious, or even zealotry about one’s favorite singer or football team. Decrease in zealotry and decrease in blind-spots go hand-in-hand. As we will see, it seems that the unread library and Dunning-Kruger effects are correlated with extremism. The wider the gulf between what one thinks one knows and what one knows, the more extreme one is likely to be. This can be reversed in some people with skill and patience.

Remember the game of telephone? One person whispers to a second person, “A few guys in yellow hats smelled smoke and ran into a building.” and the second person whispers to a third what they thought they heard from the first person, and so on until it becomes, “Two people in uniforms were seen setting fire to a building.”

That’s when no one is trying to deceive. Media outlets might turn, “A police officer who was at the Capitol on January 6th died of unknown causes a week later,” into, “A police officer dies from blows to the head by Trump-supporting right-wing extremists during the Capitol insurrection,” and they might do so to intentionally deceive you. At any rate, you may have participated in this little experiment in a college class and you may have realized how tenuous hearsay can be. Because you are human, this realization probably didn’t change your thinking permanently.

Let us say you witnessed a short but somewhat chaotic event with your own eyes and that the event was also documented from various angles with live video broadcasts. You could later watch all these videos carefully, slowing them down or pausing them if need be. You could gain a very accurate picture of the event in question. But you can’t witness everything in person nor are events always so so well documented. Sometimes there is nothing but hearsay of hearsay of hearsay. Much of what we think we know is somewhere between these two extremes of very certain and very uncertain.

If you think about it, you realize that ultimately, the only thing that you know for sure is that you are aware right now. You could be dreaming, you could be awake, you could be in some sort of purgatory, you could be just a brain wired to a reality-simulating device that is generating an illusion of reality, you could have false memories and so on. It’s the stuff of first semester college philosophy, I know, but it’s valid. You know that you are aware now. Everything else is less than certain.

In online debates over something like politics, if it is something that comes down to being either factually true or false, ask people why they think their argument is true. It could be about vaccines, election fraud, January 6th, 2021 or anything about Trump. It need not be something so polarizing, but polarizing questions tend to be fruitful and bring things to the surface that might otherwise lay fallow. With patience and skill, ask and you will see that often people believe that they know something is true when they do not actually know. They don’t know if it is true. But they believe it is true. They also believe that they do not believe it is true. They believe that they know it is true. Often they believe it is true (and that they know it is true) because others have told them it is true.

The key is to ask them how they know what (they believe) they know. You may have to ask, “…and how do you know that?” multiple times. Think of it as tracing a chain one link at a time. Often it will seem as like an endless chain of belief hanging from nothing.

Often, when it becomes too clear that this is so, the person will stop answering the questions and say something to the effect of, “Look, I just know it, ok? I know what I know. You’re just repeating a question. This is stupid. Just drop it. Would you ask me how I know the sun rises in the morning?” as if something they have no first hand knowledge of is about as certain as the dawn.

Many people would say that they know Mike Lindell’s Cyber Symposium proved that there was election fraud or that they know that it did not prove that there was election fraud. How many of them, if any, actually know. They’ve read social media posts about it, looked at memes about it, maybe even read a bit of what commercial media reported about it. But almost no one has examined it all carefully for themselves and fact checked it, where need be. Yet, many will say they know. It’s the unread library effect.

Ask them why they think it is true.

I have asked such questions to many people in many discussions about polarizing issues. Sometimes people respond with valid evidence. Ideally, they would present evidence that is sufficient to prove their case if it were argued in a court of law. Sometimes their “evidence” is ultimately unsubstantiated claims from questionable sources. Often, they offer no evidence, only assertions.

I would not do this with friends or family unless you want to drive them away.

It helps to think of these things as if you were an auto mechanic fixing an engine or a juror in a criminal court case. Perhaps ask yourself if the evidence you base your belief/knowledge on would be sufficient, in a fair trial, to convict a person of murder. Would you be sure that you made the right decision if you were on a jury? Assuming you are a healthy, empathetic human being, would it weigh on your conscience if someone were convicted because you voted that they were guilty based on the same level of evidence? Beyond a shadow of a doubt?

With that, I would like to share with you the following passage from How to Have Impossible Conversations: A Very Practical Guide by Peter Boghossian and James Lindsay (Hachette Books, 2019)…

A Common Fallacy: “Someone Knows It, So I Know It”

A philosopher and a psychologist, Robert A. Wilson and Frank Keil, have researched the phenomenon of ignorance of one’s ignorance.1 In a 1998 paper titled “The Shadows and Shallows of Explanation,” they studied the well-known phenomenon of people who believe they understand how things work better than they actually do.2 They discovered our tendency to believe we’re more knowledgeable than we are because we believe in other people’s expertise. Think about this like borrowing books from the great library of human knowledge and then never reading the books. We think we possess the information in the books because we have access to them, but we don’t have the knowledge because we’ve never read the books, much less studied them in depth. Following this analogy, we’ll call this fallacy the “Unread Library Effect.”

I would add that one must consider the potential motives of the “authors” of the “books” in the “library”. Whereas some authors have no reason to lie about a given subject, the authors of a book about a controversial topic may. They continue…

The Unread Library Effect was revealed in an experiment by two researchers in 2001, Frank Keil (again) and Leonid Rozenblit; they called it “the illusion of explanatory depth” and referred to it as “the misunderstood limits of folk science.”3 They researched people’s understanding of the inner workings of toilets. Subjects were asked to numerically rate how confident they were in their explanation of how a toilet works. The subjects were then asked to explain verbally how a toilet works, giving as much detail as possible. After attempting an explanation, they were asked to numerically rate their confidence again. This time, however, they admitted being far less confident. They realized their own reliance on borrowed knowledge and thus their own ignorance.4

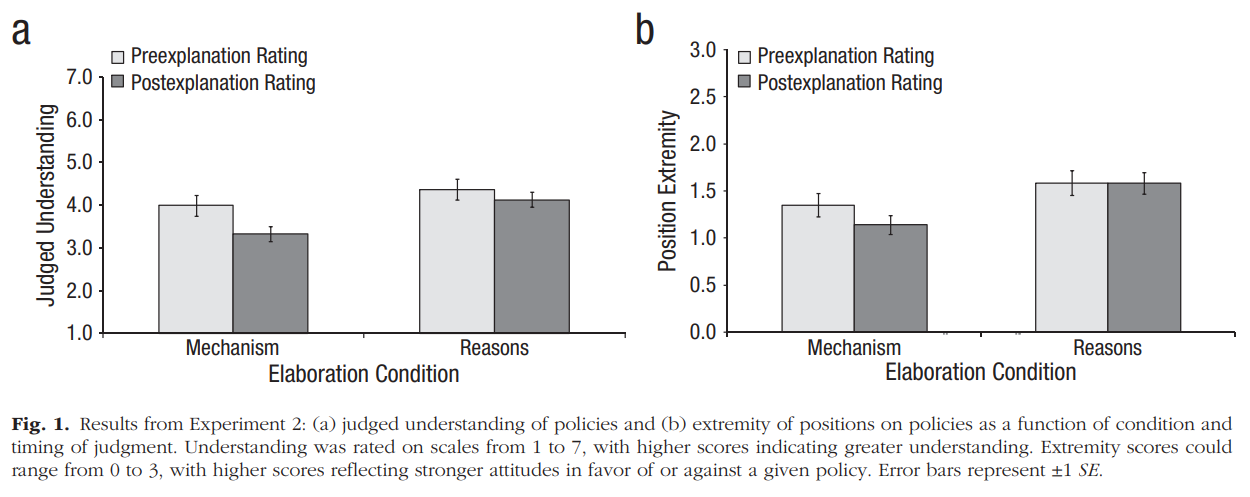

In 2013, cognitive scientists Steven Sloman and Philip Fernbach, with behavioral scientist Todd Rogers and cognitive psychologist Craig Fox, performed an experiment showing that the Unread Library Effect also applies to political beliefs. That is, helping people understand they’re relying upon borrowed knowledge leads them to introduce doubt for themselves and thus has a moderating effect on people’s beliefs. By having participants explain policies in as much detail as possible, along with how those policies would be implemented and what impacts they might have, the researchers successfully nudged strong political views toward moderation.5

Fernbach, Rogers, Fox and Sloman reported their findings in Political Extremism Is Supported by an Illusion of Understanding in which, I would add, they also report…

Although these effects occurred when people were asked to generate a mechanistic explanation, they did not occur when people were instead asked to enumerate reasons for their policy preferences…

…Listing reasons why one supports or opposes a policy does not necessarily entail explaining how that policy works; for instance, a reason can appeal to a rule, a value, or a feeling. Prior research has suggested that when people think about why they hold a position, their attitudes tend to become more extreme (for a review, see Tesser, Martin, & Mendolia, 1995), in contrast to the results observed in Experiment 1...

These results observed in Experiment 1, they report in the results section, suggest that as a person becomes more aware of their lack knowledge of the “nuts and bolts” of something, they hold “less extreme positions” on the matter.

Returning to where we were…

…Thus, we predicted that asking people to list reasons for their attitudes would lead to less attitude moderation than would asking them to articulate mechanisms…

…Contrary to findings from some previous studies, the results showed that reason generation did not increase overall attitude extremity, although an analysis of individual reasons suggested that it did increase overall attitude extremity when participants provided a reason that was an evaluation of the policy.

It seems only fair to highlight this finding, but it is beside my point. For this essay, I am concerned with why people think they know things are factually correct and not concerned with their values, feelings, and so on.

In their abstract they conclude…

The evidence suggests that people’s mistaken sense that they understand the causal processes underlying policies contributes to political polarization.

In other words, the more aware people are that they don’t know the nuts and bolts of something, the less polarization and extremism there is.

Returning to How to Have Impossible Conversations: A Very Practical Guide by Peter Boghossian and James Lindsay…

Modeling ignorance is an effective way to help expose the Unread Library Effect because, as the name implies, the Unread Library Effect relies upon information about which your conversation partner is ignorant – even though she doesn’t realize it. In essence, you want her to recognize the limits of her knowledge. Specifically, then, you should model behavior highlighting the limits of your own knowledge. This has three significant merits:

It creates an opportunity for you to overcome the Unread Library Effect, that is, thinking you know more about an issue than you do.

It contributes to a climate of making it okay to say “I don’t know,” and thus gives tacit permission to your partner to admit that she doesn’t know.

It’s a subtle but effective strategy for exposing the gap between your conversation partner’s perceived knowledge and her actual knowledge.

Here are some examples of how you can apply this in conversations. You can say, “I don’t know how the details of using mass deportations of illegal immigrants would play out. I think there are likely both pros and cons, and I really don’t know which outweigh which. How would that policy be implemented? Who pays for it? How much would it cost? What does that look like in practice? Again, I don’t know enough specifics to have a strong opinion, but I’m happy to listen to the details.” When you do this, don’t be shy. Explicitly invite explanations, ask for specifics, follow up with pointed questions that revolve around soliciting how someone knows the details, and continue to openly admit your own ignorance. In many conversations, the more ignorance you admit, the more readily your partner in the conversation will step in with an explanation to help you understand. And the more they attempt to explain, the more likely they are to realize the limits of their own knowledge.

In this example, if your partner is an expert in this aspect of immigration policy, you might be rewarded with a good lesson. Otherwise, you might lead her to expose the Unread Library Effect because you started by modeling ignorance. Should your conversation partner begin to question her expertise and discover the Unread Library Effect, let its effects percolate. Do not continue to pepper her with questions.

It’s worth repeating that this strategy not only helps moderate strong views, it models openness, willingness to admit ignorance, and readiness to revise beliefs. Modeling intellectually honest ignorance is a virtue that seasoned conversation partners possess – and it is fairly easy to achieve.

It is useful to keep in mind that people tend to form their positions on things like politics and religion automatically and unconsciously before they think about it consciously and rationally (if they ever do so, and often they do not). See The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion by Jonathan Haidt (Vintage books, 2013) wherein he discusses scientific research to support this. Most people don’t argue in favor of a policy because they are objective experts who have studied the policy and are familiar with its’ “nuts and bolts”. They do so due to unexamined emotions. Like fear, lust and anger, politics tends to subvert balanced judgement and indeed reason itself.

It seems it is largely unconscious and automatic emotional responses to tribal instincts that polarize us.

Asking people in such debates how they know what they think they know or, better yet, asking yourself these questions may lead to a shocking realization about how much of what you and others think they know is actually belief and not knowledge.

Its worth repeating - the point is that the more aware people are that they don’t know the nuts and bolts of something, the less polarization and extremism there is.

∴ Liberty ∴ Strength ∴ Honor ∴ Justice ∴ Truth ∴ Love ∴

Notes

from How to Have Impossible Conversations: A Very Practical Guide by Peter Boghossian and James Lindsay (Hachette Books, 2019) to the text quoted above

In a paper that appears to be the origin of the term “illusion of explanatory depth.” philosopher Robert Wilson and psychologist Frank Keil refer to it as “the shadows and shallows of explanation” (Wilson & Keil, 1998, “The Shadows and Shallows of Explanation”, Minds and Machines, 8(1), 137-159).

Kolbert, 2017; for more.

See TedX Talks, 2013. People who suffer the most from the Unread Library Effect are the best candidates for the Dunning-Kruger effect (Kruger & Dunning, 1999). The Dunning-Kruger effect states that legitimate experts (no Unread Library Effect, because they’ve read much of the relevant library!) feel confident and people with very little or no understanding (extreme Unread Library Effect) are even more confident. People in between, who have some knowledge but who are not experts, dramatically lack confidence. They’ve realized and escaped the Unread Library Effect by having learned enough to know how much they don’t know.

Rozenblit & Keil, 2002

Rozenblit & Keil, 2002

Fernbach et al., 2013.

Since extremism often goes hand in hand with entrenched beliefs, a moderating effect on political views may lead to more civil and productive political dialogue and more changed minds. Not only will civility and belief revision benefit from moderating extreme political views, but also the health of our entire body politic may improve for another reason. Extremists often accept the views of a relatively small number of deeply trusted leaders and believe them fervently. That is, extremists are gullible and easy to manipulate.

Many conservative extremists in the United States, for instance, spend enormous sums of money on guns and ammunition in response to a mere suggestion that a liberal politician might “take their guns,” despite there being essentially no strong reason to believe any such thing will happen. Left-wing extremists will believe almost anything is anathema to their values (like eating tacos on Tuesdays) if it can be made to appear as revealing racist motivations or undertones. Extremism on both sides seem to throw money at snake-oil supplements and remedies sold by people perceived as moral leaders in their own moral tribes.

Extremists are also well-rehearsed in their leaders’ talking points, deeply entrenched in their beliefs, and often literalists in their interpretations, and they vote in accordance with the dictates of their thought leaders. Moderating extreme political views can be expected to decrease gullibility and manipulability of the electorate, the benefits of which would reach into almost every corner of civic life.